John Kelly recently played the debut of a new instrument, the KellyCaster. But this musician, this instrument, are significant for more than just novelty.

It’s more than likely that you haven’t heard of John Kelly. So before talking about the instrument, it’s worth explaining not just who he is, but why he’s had an instrument named after him. John is a talented musician and songwriter who has extensive experience with multiple instruments and has recorded and played live internationally. John is also a musician with access needs. Probably a lot of people might say he’s a “disabled” musician, but I prefer the previous description, and I will explain why before the end of this piece.

John’s personal page gives a full picture of him and his work. You can also check out Drake Music, the UK nonprofit with which he collaborates. Their self-described mission is to create “a world where disabled people have the same range of opportunities, instruments and encouragement, where disabled and non-disabled musicians work together as equals.” That includes artist-led projects, like John’s KellyCaster.

However, to me, these pages don’t really do him complete justice. Meeting him in person brings this story to life. I was lucky enough to do just that at the KellyCaster launch a few weeks ago.

Meet a new instrument

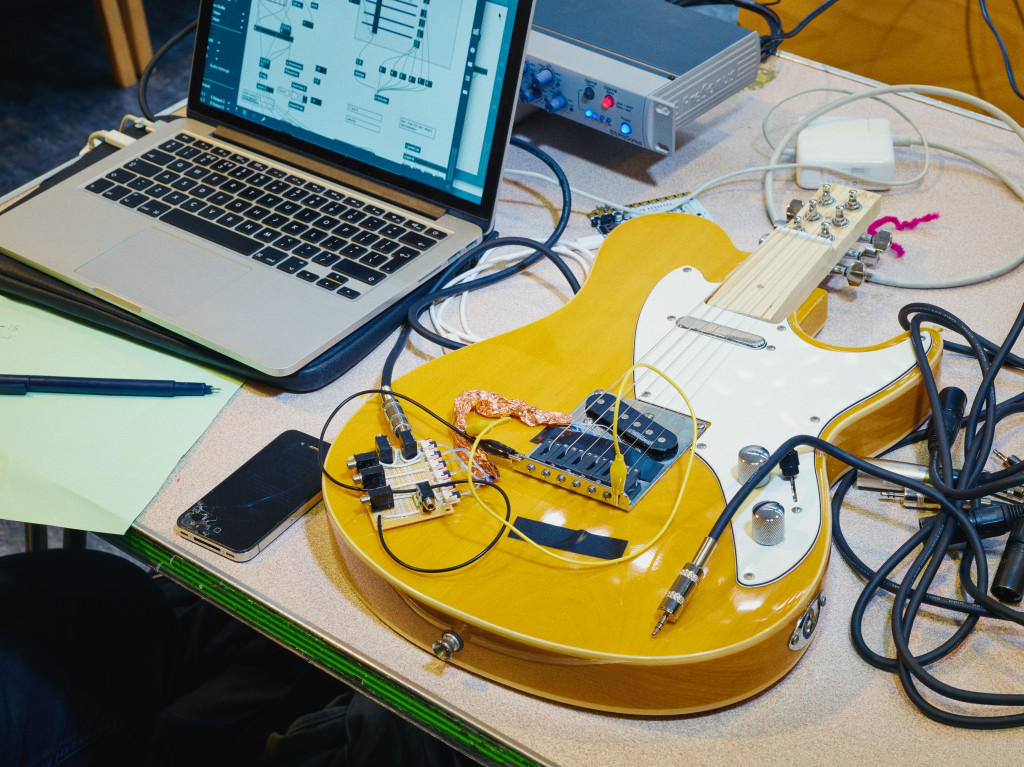

Whilst the KellyCaster might look like a slightly strange guitar, first looks can be deceiving. Just a cursory glance at the KellyCaster belies the wealth of technology that went into making it work. It’s complex and well put together specifically to serve John’s need.

John, together with a collection of musical friends, played a short set quickly had the audience dancing and singing along. It was deeply powerful, as this was a first. It was a first not just for someone playing this instrument, but for John playing any guitar live, making the previously impossible possible.

The gig showcased John playing the KellyCaster, and how it could operate as part of the band in the same way that any other instrument would. That worked beautifully — all the technology that sits behind the KellyCaster simply disappeared.

In fact, that was what really impressed me. I can’t remember when exactly, but at some point during the performance, I simply forgot that there was all of this tech making it work, and just enjoyed the gig. The KellyCaster was just another instrument. All that was left was a group of talented musicians working together to create a truly wonderful experience for their audience.

While this technology can be invisible to the audience, it’s essential to the instrument’s function. And it’s a significant achievement, the culmination of an extensive design and construction process as part of Drake Music’s DMLab programme which was funded as part of the Inclusive Creativity project.

The KellyCaster uses standard but untuned guitar strings, which are amplified using a Roland GK hexaphonic pickup. This feeds into a BELA, the embedded platform for ultra low-latency audio, using custom electronics. The code in the Bela reads the attack and sustain of each individual string and feeds this information over OSC (Open Sound Control data) using a USB connection to a MacBook Pro. A Max for Live patch reads this data and allows it to control guitar synthesis, as well as select which note or group of notes/chords is selected in each case. John maps this to a MIDI controller to allow him complete the harmonic control.

The development process

The KellyCaster was brought to life by a talented team, starting work over two years before its debut. The design idea itself came directly from John Kelly himself, who conceived and a specification for an accessible guitar, bespoke to his own unique access needs. He presented that idea to Drake Music’s DMLab meeting to invite collaboration.

Gawain Hewitt took up management of the project, and created a first prototype. The new technology in the instrument is the work of Charles Matthews, who developed code and electronics. He assembled this portion in a Drake Music accessible music technology hackathon at the Southbank Centre over a weekend in May, with input from the musician as well as Dave Darch.

There were more conventional instrumental design inputs, as well. The luthier (that’s someone who builds or repairs stringed instruments) was Jon Dickinson, who did an incredible job on the bodywork.

The innovative resulting instrument won the hackathon, and was featured in the Independent’s ‘I’ paper that same week.

Changing how we think about meeting needs

As I hope you can see, it takes time, creativity, and dedication to get this kind of outcome, and this is just one example of Drake’s work with bespoke instruments. Drake Music’s DMLab is dedicated to the research and development bespoke instruments for disabled musicians, instruments that make a real difference to those individuals’ ability to work and to perform live. Drake’s DMLab have used this process for a number of commissions, and there are more in the pipeline that I hope to be talking about over the next few months.

At the start, I described John as a musician with access needs rather than as a disabled musician. That’s a really important point in understanding this instrument. It was built in response to an access need. When that need is met, John is still a musician, but his needs from the instrument have been satisfied. Job done. However, if I were to describe John as a disabled musician, we might see the KellyCaster as a solution to a problem. Whilst it’s great that we’ve fixed the problem, we would still refer to John as a disabled musician, and that could infer a disparity with other musician – one that simply doesn’t exist.

It might seem like a very subtle point, but I believe it’s a very important distinction. By developing the KellyCaster to meet John’s need, the team as a whole have removed a barrier that John faced. With technologies like this, many more access needs could be addressed and barriers removed for a range of artists. We can move away from seeing musicians with access needs in terms of their disability, and understand them in terms of their talent and creativity. That has to be a better model.

The KellyCaster is making a big step forward for accessibility. I don’t know what comes next or how it will be taken forward. But it has a huge potential to be applied in other instruments, devices and contexts. I’ll be staying close to Drake and the team to see what happens next. As and when it does I’ll let you know.

A very big thank you to Emile Holba for the photos used above.