The electronic music analog to visual media’s question “is it art?” is clear. “Is it really a musical instrument?”

Ableton will this week officially launch its Push hardware with Live 9; we’ll have an online exclusive review alongside that release. I know that the company is fond of calling it an “instrument.” For a profile by the German-language magazine De:Bug, Ableton CEO Gerhard Behles even posed with a double bass, the Push set up alongside. The message was clear: Ableton wants you to think of Push as an instrument.

We’ll revisit that question regarding Push, but this isn’t only important to Ableton. The question of whether something is an instrument seems to matter deeply to a lot of people, musical experts and lay people alike. So, let’s pick up that question to get the conversation started.

Digital music technology, most fundamentally, creates a level of abstraction between what you’re directly manipulating (such as a knob, mouse, or touchscreen), and the resulting sound. As such, it challenges designers to provide the feeling of manipulating something directly, making those abstractions seem an extension of your thoughts and physical body. It can also arouse suspicion and confusion in audiences, who may be unsure of what they’re really watching.

Because traditional instruments are bound by acoustic sound production the physical world, they don’t have the same problem of abstraction that digital (or analog) instruments do. But beyond just the sound source, I think people do respond to the activity of instrumental musicianship. We can think of that as the notion of playing a musical idea “directly” – making a specific and discrete connection of motor movement to musical output.

Even in acoustic instruments, there’s a spectrum of how “direct” the physical control of sound may be. The only instrument which you play without physical/mechanical intervention or abstraction is your own voice. All other instruments provide some degree of intermediary. This includes aids to finding certain pitches (frets, piano keys), and the mechanism by which you control sound. It’s not the same as designing a GUI, but it is still interface design, and it makes any performance a dialog with the instrument as an object.

Where this is potentially different from electronic instruments is that there is a clear, ever-present relationship between each gesture you make and the sound that is produced. Digital instruments can work that way, but they’ve also introduced a whole new category of interaction that didn’t exist in complete form before.

Meta-performance, composition as play

Composers and conductors had experienced these kinds of interaction, though not in the same way or all at once. Composers using paper scores can construct musical materials for other musicians, imagining more than what they can play themselves. They have (hopefully) heard those results, too, though they haven’t been able to control them in real-time. Conductors working with acoustic musicians can make gestures, interpreted by the human players, that shape music without directly making those sounds. But they can’t generally re-compose the music itself on the fly. (That is, they can impact parameters of expression or tempo, but not much more than that. Still, you can see why the roles of compose and conductor often go hand in hand – kudos, Leonard Bernstein.)

Computers do more. You might play a single line and have it automatically harmonized, or control a set of parameters that algorithmically manipulates musical materials, making composition into a kind of performance.

It’s this end of the spectrum that creates the most confusion. How much impact are you actually having on the music? The “conducting” metaphor, while woefully incomplete, is actually somewhat apt for describing the issue. Ask a violin section about a conductor they didn’t like, and they’ll often tell you the orchestra stopped paying attention and started playing the music themselves.

But it’s also this spectrum that can make digital music interfaces so appealing. The role of musician and composer are now effectively merged. The choice of where to sit on this spectrum is now your choice.

Controller or instrument?

“Controller,” then, might sit at the far end of the spectrum; the very name suggests a remote control for a software model. “Instrument” is a nicer term because it suggests you’re “playing” – not simply controlling parameters, which has no explicit musical meaning.

But there isn’t a clear dividing line. That’s why some people wondered last week just how much a Push instrumentalist was playing of The Flight of the Bumblebee. (In a simple, player-piano sense, in fact he was playing only about half of the musical line.)

The question of instrument-ness may be more elusive. If you play a line directly, each gesture controlling sound, you certainly fall in with the more traditional instrumental definition. Sure, triggering samples doesn’t give you timbral control of every nuance of a note – but neither does a piano. (And I love the piano.) But, at the same time, you might have at your command even greater musical detail that an instrument can’t provide. Somewhere, then, instrument-ness is about physical and emotional engagement. And that means that, absent a hard definition, we may find some of the control of larger musical parameters to have an impact, too.

Playtime

Listen closely to terms, and you’ll get some clues. People talk about “playing” or “controlling,” for one – and I think, for all the value of controllerism, “play” is what many people most want personally. (Forget the audience – it may be what they want the most from their own experience.)

At least we can begin to understand that, on the computer, having physical engagement and direct motor control over details of the performance – whether small-scale parameters or large – matters. And we can assume that people are biased by a traditional sense of what “playing” is: playing multiple lines means more people, or at least more hands, so the soloist is often expected to directly control something.

I don’t think there’s a quantitative measure for “instrument-ness.” But qualitatively, there are plenty of shared concepts from which to begin. Those concepts matter so deeply to music, there’s also a great deal of value to be had in conversation and reflection.

Just don’t forget to play.

We’ll follow up more on this soon (and there is some academic writing on the subject I can recommend); so stay tuned.

Further Reading:

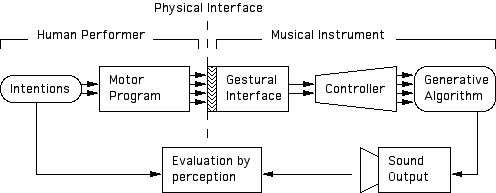

I’m particularly fond of two articles by David Wessel (with Matt Wright and Michael Lee) that look at the entire system of human / computer interaction as an instrument. (See image, here.)

From 1992, “Connectionist models for real-time control of synthesis and compositional algorithms” was an ICMC paper with Lee, drawing on neural research.

More recently (2002), “Problems and Prospects for Intimate Musical Control of Computers” was published in Computer Music Journal. The second of these gets more into the details of how to make a better instrument, improving expression and user engagement by reducing latency, improving intimacy, and providing greater continuous control over sound (and therefore improving on the piano, not just MIDI). It also deals with learning curve (providing a low barrier of entry but high potential for expertise) and even some implementation particulars with OpenSoundControl (OSC). But, as here I’m interested in much with the paradigm, I want to highlight this paragraph:

Unlike the one gesture to one acoustic event paradigm our framework allows for generative algorithms to produce complex musical structures consisting of many events. One of our central metaphors for musical control is that of driving or flying about in a space of musical processes. Gestures move through time as do the musical processes.

One example of that “flying” model is Tarik Barri’s performance, featured in the first half of our MusicMakers showcase video from last week. Tarik’s work involves flying through the musical structure; he even uses a device called the SpaceNavigator as a controller. (One reader commented in that story on visual spectacle; it should be noted that Tarik often works in visual media specifically, and is now touring with Atoms for Peace.)

But what’s important about the story above is not that all of us need to create fly-through music with joysticks or steering wheels. It’s that the paradigm in this case can cover a range of scenarios. Which you choose is still very much up to you, but now described in a way that different kinds of musicians can carry on an intelligible conversation about what they’re doing.

This diagram from Wessel and Lee sums up their thinking:

Via comments, Evan Bogunia shares his thesis paper:

Computer Performance: The Continuum of Time and the Art of Compromise

I’d be happy to read other research, though if we covered all the research into instruments, well, that’d be a lot — so let’s say other research in working out how to define the question, rather than the answer.