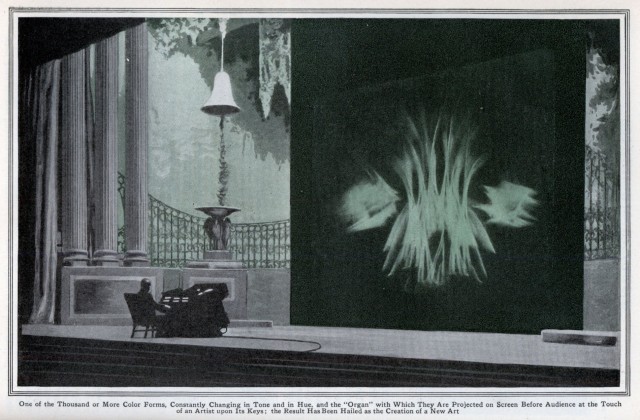

Long before trippy visualizers and computer animation, before liquid light shows or laser parties, Thomas Wilfred was building organs for visuals. He called the

art they produced Lumia, and the instrument Clavilux – a keyboard for light.

That first instrument was built all the way back in 1919. But unlike a lot of the spectacles of the era, this one is still hypnotic today, even after all the advances of cinema and computing.

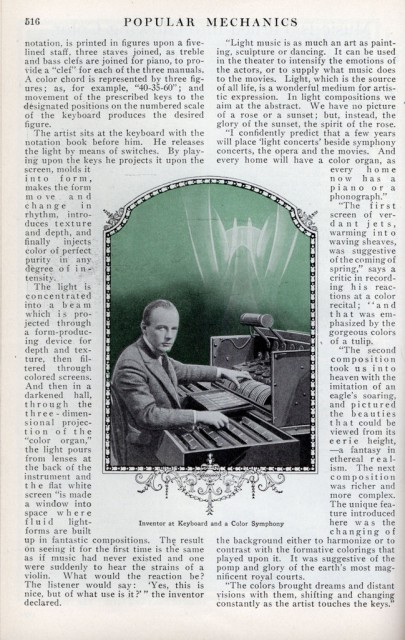

Drawing on a tradition that included displays of fire and fireworks, and the ability to place sound “at the command of a skilled player at a piano,” Wilfred found a way to produce a visual instrument, apparently after first toying as a child with prisms.

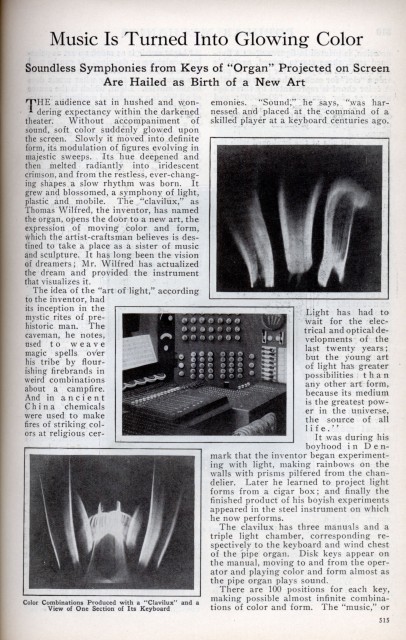

The actual mechanism is strikingly sophisticated. The Clavilux beams light through lenses and tinted screens to reshape abstract patterns of colored light.

Depending on the variant, the organ included three manuals. Each key can then be set to one of 100 positions – a digital system not unlike MIDI, in fact (with 128). In place of just a note head, the keys would have chords with numbers, with lines on a staff as on a piano.

The inventor’s predictions were more than a little off, as he imagined this abstract art form would take its place next to music concerts and moviegoing in “a few years.” But now, in 2015, it seems its time is right. The culture is ready. And no, not just through the ingestion of drugs – I heard a talk once by the Joshua Light Show where the creators were quick to say that they stayed sober; they had to in order to perform. These techniques produce optical stimulation without any substance. You just need an audience ready to embrace abstract dances of light.

And a new generation of artists are rediscovering these techniques. I can imagine two motivations. Firstly, if performances are meant to be transporting experiences, away from our everyday world, there’s a clear desire to escape the screens that now dominate that world – computer, tablet, TV, phone, and public displays.

Secondly, visual artists are now so comfortable with computer techniques that augmenting their skills with optical techniques is possible. And with a full understanding of what digital media can and can’t do, one finds a new appreciation of the unique possibilities of the optical. (Just don’t say analog, which in music and visual synthesis means specific manipulation of voltage: optical is its own, separate field providing all the potential of lens and lighting.)

But even more than those motivations to go optical, this stuff is singularly beautiful by any standard. Now, audiences are ready for abstract visual art in motion. Just as sounds that would once have started riots are welcome, that music that breaks entirely from previous tradition is festival fare, we live in a world where we’re ready to process visual stimulation without narrative or figurative function.

See: Birth of Music Visualization (Apr, 1924) [Modern Mechanix, an excellent blog, from way back in 2007]

The black-and-white images here come from an April 1924 article on the technique. The videos are from his Lumia series. You can buy DVDs (and even institutional licenses for public performance) from clavilux.org.

The videos are modern restorations.

Wilfred even envisioned a “home” tabletop edition called the Luminar. Yes, please. I want this a lot more than I want a TV.