Quick: you need to produce a music score. It needs to look really great. The deadline is looming. You’ve lost your serial number for [insert program here]. What do you do? The answer might surprise you.

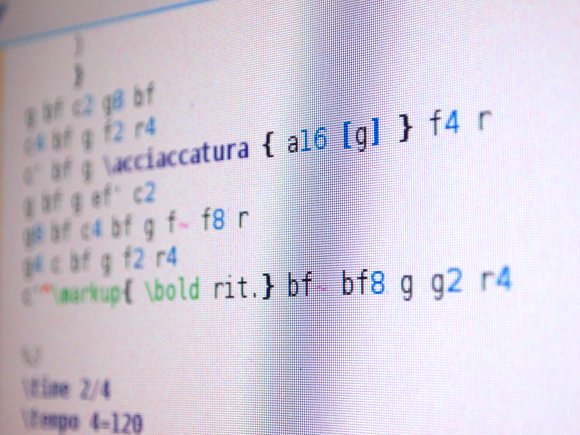

Lilypond is something of a cult secret in music notation circles. It’s free software for high-quality computer engraving, it runs on any platform (Mac, Windows, Linux), and it produces exceptionally good-looking output, often exceeding leading commercial programs in particularly tricky notational situations. But it could easily scare off beginners, because it isn’t necessarily graphical software. The tool generates its output from text files, a bit like the way in which a Web page is rendered from an HTML file.

What beginners don’t know is that text entry doesn’t have to be slower or more daunting – especially if you choose a tool that assists you in the entry process.

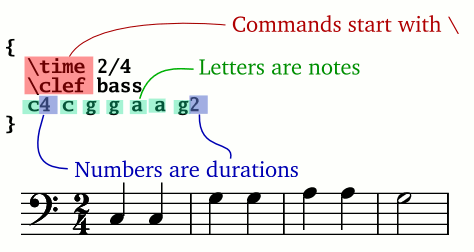

Lilypond’s language for basic music entry is actually reasonably simple. If you want a g flat, for instance, you just type “gf.” (Note: you will probably need to adjust Lilypond for your native language to get an abbreviation for “flat” that makes sense to you! Hint: “flat” is in English.) To change rhythmic durations, you use a number, so two eights followed by two quarter notes would look like “c8 d e4 f.” Because it’s text-based, you can be explicit about what you want, which avoids some of the pitfalls of graphical entry methods. If text is to be attached to a specific note, you specify which note in your text file. Most importantly, this means that entering and arranging notation doesn’t get any harder as the score becomes more involved. For complex measures with densely-packed material, or tricky notations from early music to modern composition, Lilypond continues to handle layout and rendering automatically, without intervention – just at the point many graphical programs will have you pulling out your hair.

Lilypond “Switch” How-to Crash Course

Entry itself can therefore move really fast, especially if you like to sketch out an idea on paper (or in a MIDI file) first. I recently completed my first score in Lilypond, and was surprised that – after the initial hour or two of entry – I started to really like it. Getting the first few bars in was a bit tricky as I got the hang of entry, but then, to my surprise, finishing the score went as fast or faster than it had in other programs.

Find the Right Tools

That isn’t to say you won’t want some help. Music notation is always involved, because of the sheer quantity of notational conventions used – even for fairly simple musical contexts. And while text entry makes copying fast, you’re likely to want some MIDI playback and entry assistance. In fact, I’d wager the quality of your experience with Lilypond will depend on choosing a front-end tool you like.

I experimented with various tools on my Ubuntu install, including some graphical programs that can read and write Lilypad files. If anyone is interested, there are a number of programs I can recommend you don’t use. In the end, I found that what I wanted was essentially a text editor – so I could take advantage of the speed of Lilypond’s text-based language – but with plenty of shortcuts so that I’d never get lost trying to look up how to input a symbol.

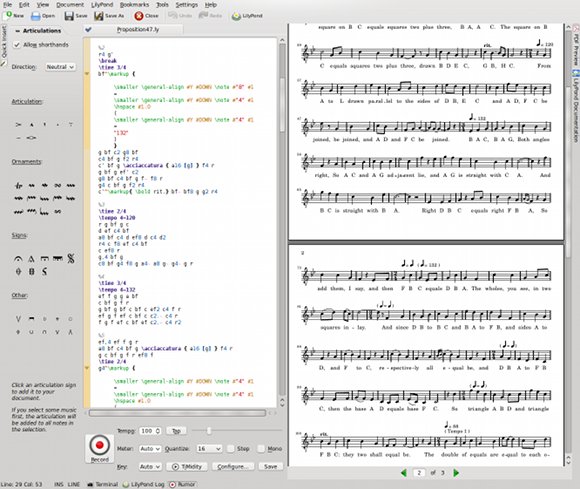

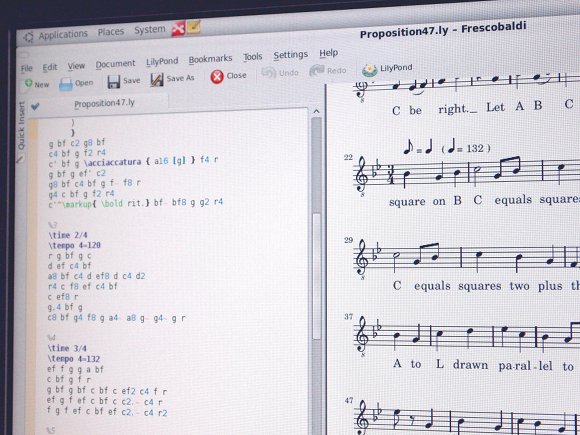

Frescobaldi was a real pleasure to use, if you have a Linux install. (That’s the case for now; efforts to port KDE and Python should mean Mac and Windows versions aren’t far off.) It’ll install a lot of dependencies on a stock Ubuntu install because it relies on KDE, but it’s a nice all-in-one tool. A PDF preview accompanies your text so you can see what you’re doing, and by clicking on a note, you jump to the correct place in the text. There’s instant access to online help and notational references. The nicest feature is perhaps the MIDI input using Rumor, which worked out of the box with an M-Audio USB MIDI keyboard I connected.

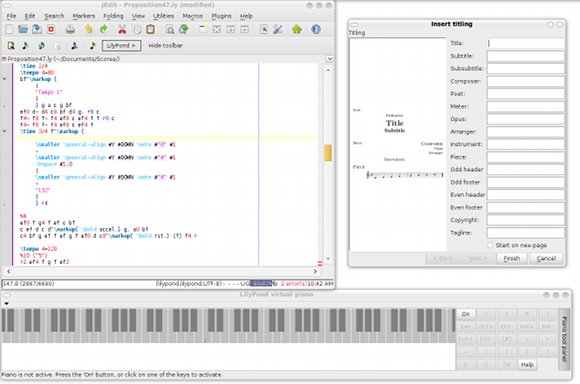

The other best-of-class tool I found is none other than omni-platform text editor jEdit, with the LilyPondTool add-on (Mac, Windows, Linux). (Thanks to a Twitter friend for the tip; thanks to Twitter’s terrible archiving, I’ve lost who you are, so say hi in comments?)

Grab jEdit, and perform two steps:

1. De-uglify jEdit. Yes, that default skin is hideous, and doesn’t look like any OS you’ve seen in the past ten years. Choose Utilities > Global Options > Appearance > Swing look & feel, and set it to something native for your OS. Reboot, and take a deep breath.

2. Install the plug-in. Incredibly, it’s a default option. Choose Plugins > Plugin Manager > Install > LilyPondTool.

jEdit’s LilyPondTool does a lot of what Frescobaldi does, with wizards for setting up scores and changing parameters and various clickable shortcuts. But it benefits from putting this functionality inside an extensible, standard text editor, which means you can do anything with LilyPondTool that you can with jEdit. And there are simply more options – there are more quick menu shortcuts for symbols, tweaks, and all the other little things you have to do in notation that you don’t realize you have to do until you get halfway through a score. That makes LilyPondTool a bit friendlier to beginners. It doesn’t have MIDI input as Frescobaldi does, but it does have MIDI playback. You even get nice tools for making templates and OpenOffice-based hyphenation of lyrics, plus a virtual on-screen keyboard to aid with entry.

http://www.jedit.org/

LilyPondTool

One part of the process I didn’t quite work out was the best MIDI import tool. There’s a simple Python script that ships with the Lilypond distribution, and it can be called from tools like jEdit+LilyPondTool. But converting MIDI to notation isn’t a simple task in any tool, so I’d have to research this further. Doing note entry in a proper MIDI sequencer, then adjusting the engraving in a Lilypond editor like jEdit or Frescobaldi seems a terrific workflow, though, if anyone has found a process that works for them.

What you might miss…

So, how does a free tool like Lilypond stack up against the newest version of, say, Sibelius?

Even if you’re a seasoned Sibelius user, I highly recommend doing at least one score in Lilypond, as it’ll give you a window into how Sibelius works, and the issues that arise in computer notation. I believe Lilypond may have even helped influence modern versions of Sibelius with its approach to engraving, though that’s only from memory – don’t quote me on that.

You will see some advantages of Sibelius. Sibelius’ graphical layout means there’s no separation between what you see and what you edit, and one big edge of the Sibelius engine from the beginning has been its ability to reflow even huge scores almost instantly. That visual process could become part of your compositional workflow, too, with on-screen clipboards for ideas and quick playback of ideas. Sibelius has also done a lot recently with DAW-style tools for MIDI, live tempo tapping, integration with ReWire, and so on. That makes Sibelius a powerful tool for creating high-quality playback right in the score.

Nice as Lilypond is, I certainly have an easier time imagining teaching students notation with Sibelius than with a text editor.

Advantages of the Lilypond approach

I commonly hear odd, defensive barbs about free software, especially in the music community. People will casually drop statements like, “but the open source community doesn’t innovate. They just rip off commercial software. And it’s just not as good.” As near as I can figure, this entire argument is often based on one or two bad experiences with OpenOffice a few years ago.

Now, some of this defensiveness comes from the fair perception that discussion of free software often centers more on philosophy than practicality. And there, I agree. Software is a tool. Philosophy matters, but you ought to be able to look at tools in more or less objective terms. You ought to be able to like using the tool.

Lilypond is a perfect counter-example. It is innovative software, period; now well over a decade old, it’s well-respected in the engraving community. I’ve been surprised to find out how many people use it, and they do so because it saves them time and headaches and they like the output.

It’s also just plain different from the commercial offerings. Its free nature means it can do things that commercial software doesn’t even try to do. (Can you imagine a major vendor unveiling a text-only notation app? Didn’t think so.)

As with any design, this means some trade-offs. They aren’t as simple as “Sibelius and Finale are for casual users; Lilypond is for hard-core geeks.” On the contrary, I found some real advantages.

Text input means backup, file exchange, and tracking revisions becomes a whole lot easier. Lilypond’s output is more like traditional engraved scores than anything I’ve seen from Sibelius or Finale, even when swapping fonts in those packages. Lilypond is uniquely equipped for doing early music notation; it makes a lot of alternative notations as easy as modern notation. Sure, that sounds like an “advanced” feature, but it’s an “entry level” feature if you happen to perform or research early music.

Also, despite improvements to things like Sibelius’ “magnetic layout” and other automated features, I find that even the newest versions of these apps still require a lot of tweaking after the fact. Lilypond still requires “subjective” tweaks – adding a page break where you want one, for instance – but I tried some tests with bars of music that broke my favorite commercial tools, and Lilypond was very hard to stump. There’s also the simple fact of the matter that with graphical tools, it’s easier to screw up the notation yourself, by attaching text to the wrong note or dragging something slightly out of place. Those changes are hidden in the graphical view, too, whereas they’re explicit in the textual score.

I don’t think one approach is necessarily better than the other. The point is, you need both. Something like Sibelius or Finale is just not going to evolve in free software. But something like Lilypond isn’t going to evolve in commercial software.

You also don’t have to choose one or the other. Thanks to MusicXML, an interchange format, you can exchange files between Sibelius or Finale and Lilypond easily. If you work a lot with scores, it’s worth a download – and the price is right.

And I don’t believe Lilypond is “for geeks only.” Give yourself a simple job, like a lead sheet, and pick a solid tool. Give it a real try, with a couple of evenings to get used to the language. I think whether you like the results will have more to do with personal preference. But I’m glad Lilypond exists, and I think you may find it’s something you want to add to your arsenal, even if that arsenal also includes one of these other tools.

For good measure, here’s a visualization of the open source contributions to the project.

code_swarm: LilyPond apr 23, 2010 v2 from Paco Vila on Vimeo.

Keep up with news from the project, and some good tips, at:

http://news.lilynet.net/

Share your experience

If you want to give this a try, I recommend both the jEdit and (for Linux) Frescobaldi routes. Each has links to Lilypond tutorials and documentation right in the program. I’ll try to work out a quick tutorial at some point, too; I’m planning a bigger set of scores and am going to give Lilypond the old college try.

Worked with Lilypond? Found a tutorial that helped you out? Got some tips? Trying it out and need help? Do share.

By the way, that score I worked on will be premiering as part of a party with operatic and musical theater types Monday in New York. Alongside digital music made by computers, it’s nice to get to work with humans, too, which is why I suspect notation will be with us for a long time to come.

New music party, NYC, Monday night 5/17