Music software is at its best when it goes beyond cookie-cutter regularity, and spawns something creative. And sometimes, the path there involves retooling how that music is made.

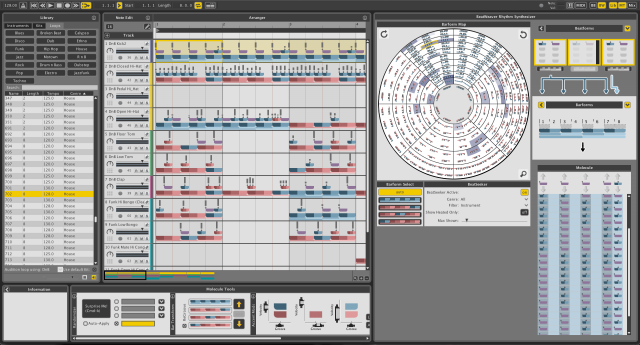

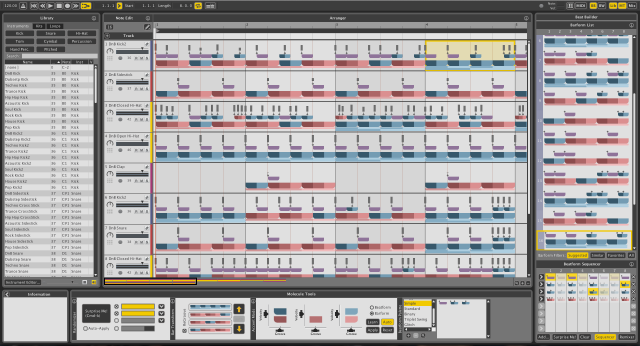

That’s why I’m pleased to get to share this interview with WaveDNA. Liquid Rhythm is something unlike just about anything else in music software. It looks like a music theory class collided with a mandala. In colored patterns, arrayed in bars and wheels, you can produce all kinds of new rhythms, then integrate deeply with your host software. If you use Ableton Live, the integration goes further still. Whether you’re using Drum Racks or notes, you can automatically see what pattern goes with what, working in real-time with everything visible as you go. There’s a whole suite of tools with more than enough of what you could explore in any host. (Then, in Live, it just gets crazier.)

You can randomize and remix and shift, for quick ideas. (They had me at ‘randomize.’) Or, if you’re brave enough to enter the worlds of beat and pattern control, you can use the tools for fine-grained production of unusual musical ideas.

The suite:

Plug-ins, patches. VST, AU, RTAS for any host. Or Max for Live for Ableton Live, now with full integration with Ableton Push hardware.

Palettes of rhythms. Paint with patterns, or make patterns in pitch and rhythm from clusters, in BeatBuilder.

Dial up rhythms. BeatSeeker displays various genetic possibilities of patterns in a huge wheel.

Accents, grooves. Design grooves and velocity by color in an accent editor, or re-groove existing materials with something they call GrooveMover.

MIDI without a piano roll. Yes, this common interface has become tyranny. It’s tough to describe, but they have a different view, one that provides manual control in a unique interface that goes its own direction – more like a genetic cell than a piano roll. (See the video, as it’s easier to see than write about.)

Integrate with Ableton Live clips.

“We’re a music software company that makes no sound,” say the creators in the interview here. Instead, they let you put rhythms where they don’t normally go. Sounds good to me.

Here’s a look at how their in-line editing works, and how the musical concept functions:

And a bit on how the beat generation process works:

And for Ableton users, here’s a look at that integration in Live 9 Suite:

We’ve been hearing from readers that many of you are tired of standard step sequencing interfaces. (I still like them sometimes, so watch this week for my review of the 2×8 grid of the BeatStep from Arturia, but I hear you.) So, this seems the perfect time to bring up WaveDNA – it isn’t four-on-the-floor. It’s… everything, on the floors, walls, ceilings, whatever.

I had hoped to write about WaveDNA for some time, but it was so vast, I never quite got the window. Fortunately, recently CDM’s own Marsha Vdovin, veteran journalist and music tech industry insider (among other roles), wrote an interview with the creators for Cycling ’74. (While it works as a plug-in in other hosts, the toolset is also a fine showcase of Max when integrated with Ableton Live 9 Suite, so it’s a natural to talking about Max.) Full disclosure: Cycling commissioned Marsha to write this story, and provided CDM with permission.

Full details (a free demo is available):

http://www.wavedna.com/product-information/

And I obviously need to get deeper into Liquid Rhythm. It makes me … almost a little afraid. Like I might disappear for some time and not be seen. But I could use some studio time. So if this story brings up questions, let us know. (And since some of you use Max and other patching environments, I’m sure the developers would be happy to talk to you about that. Now I have to make my stupid-simple generative rhythm patch work in Max for Live next…)

Here’s Marsha. -PK

Wave DNA is a Toronto-based company that has achieved great success with their Liquid Rhythm software. This innovative beat generator, which enables users to access the building blocks of ten quadrillion rhythmic patterns, integrates seamlessly with Ableton’s Live and is now updated to version 1.3.4 which introduces Ableton Push hardware integration. We sat down with the creators to discuss their use of Max in the inspiration, development and prototyping of Liquid Rhythm.

From left to right: Dave Beckford – Lead Inventor & Vice-President of WaveDNA. Chris Menezes (behind Dave) – Junior Developer. Adil Sardar – Lead Developer. Hui Wang (on laptop screen) – Senior Software Developer. Peter Slack (far right) – Senior Software Developer and IT Manager.

DB: David Beckford, Lead Inventor and Vice-President of WaveDNA.

PS: Peter Slack, Senior Software Developer and IT Manager.

CA: Chris Amazis, Junior Developer.

HW: Hui Wang, Senior Software Developer.

Marsha: Can you tell me tell us a bit about Wave DNA and your products?

DB: WaveDNA is an entity to commercialize our Music Molecule technology. The Music Molecule provides structure to raw MIDI by grouping notes into modular containers. The containers preserve whether the notes occurred on strong or weak beats, for example, and in this way, the Music Molecule can capture relationships between related notes. Standard notation can capture some of these relationships, but not in the same modular, re-usable way as our system. We believe our system is more suited to today’s production environments, and doesn’t require a textbook to grasp.

Now, the problem, that I found 25 years ago when I was studying composition and first working with MIDI, was that these two, standard notation and MIDI, can talk past each other in certain ways. There needed to be a way to take concepts from both and work towards a productive middle ground. It took an evolution from that point to get things going.

So we’re a pattern language that can analyze and create music.

How did you guys start using Max/MSP?

PS: Max was Dave’s original architectural choice. I think the graph model or design pattern approach in Max sort of lent itself to rapid prototyping, and Dave had experience with earlier products that he invented with Max. He used it back in the days when he was working at the University of Toronto Mississauga with collaborators that we still work with through Rhyerson’s SMART Lab. So even at that time, we’re talking about seven or eight years ago, Max was state of the art and very useful.

Personally, I wasn’t aware of Max before I came to work with Wave DNA. So I learned from tutorials on line and just hands-on monkeying around with it.

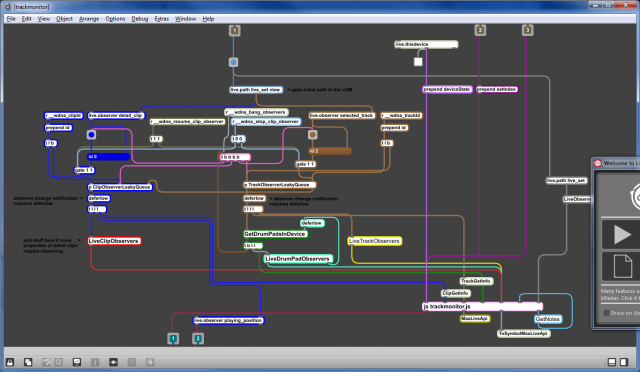

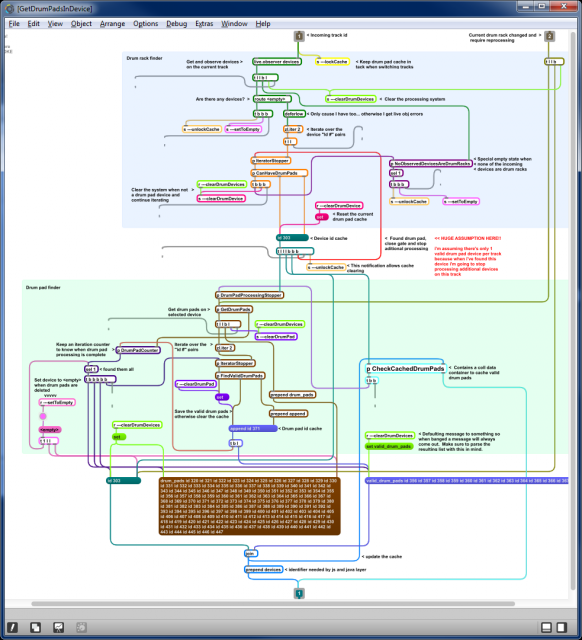

DB: Peter manages the architecture and the substructures of liquid rhythm. He makes all of the end processes talk. And he was the initial person who pioneered the Ableton, Max for Live Bridge implementation, which is really popular among our customers right now.

So you used it to prototype your product?

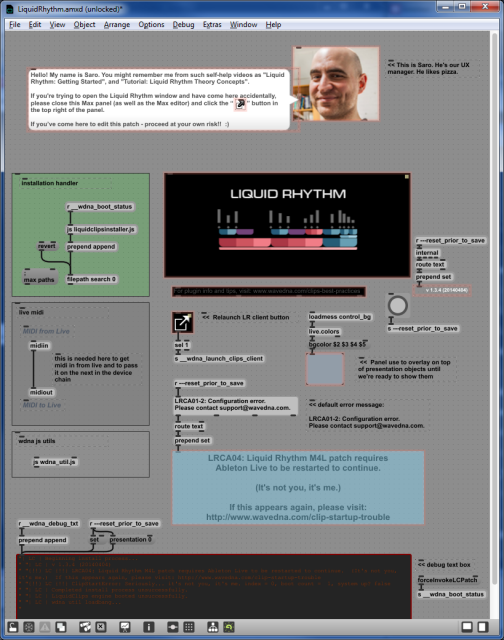

PS: Yes. Our prototypes were purely in Max. We had other elements of the product that Dave developed in Java. So my task was to sort of marry both of those together, so that the audio side of it was prototyped in Max, purely. And it’s actually part of our production product.

Which part of your final product is still in Max?

PS: Our final, what we call the Audio Engine, which is a separate process, and it’s Max code. It also has our WaveDNA brains, Java brains, embedded into it.

We still use Max to prototype. We have new products that we’re prototyping with Max right now. Dave is working on a prototype that’s pure Max. We’ll eventually integrate it with the rest of the system, including the Java.

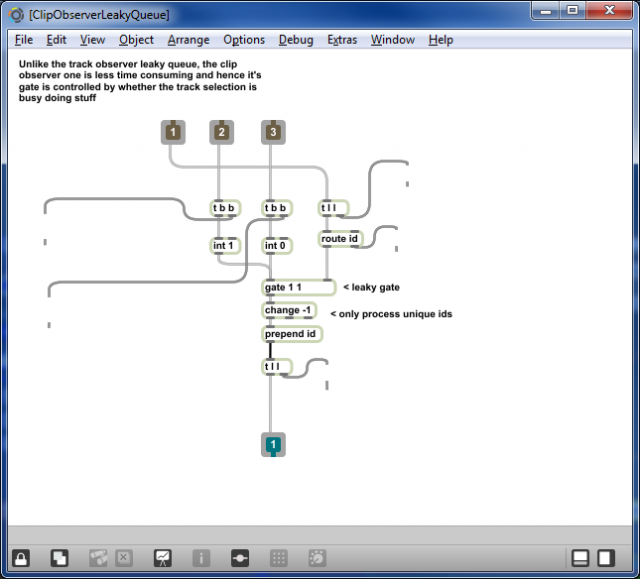

One of the original ideas, even five years ago when I came on, was to integrate the WaveDNA product with Ableton’s script-ability in Max for Live. Then, about a year and a half ago, we prototyped what we call Liquid Clips and it’s using the Max for Live scripting engine in Ableton Live 9.

We basically took our audio engine max patch, plopped it into Ableton’s framework, and the product was prototyped within about a day and a half with a few adjustments. Of course, we’ve done a lot of work since then to optimize and fine-tune it to the product it is today, and that is the work of Hui who continues to maintain that product.

So Max has not only been a preferred prototyping platform here at Wave DNA, but it also ends up in our final products, in various forms.

And Hui, you’re the Senior Software Developer. How did you get started with Max?

HW: When I started off here at Wave DNA, I actually didn’t know much about musical concepts nor even heard of Max. I came from a low-level programming background and when I was first introduced to this ‘magical language’ where you connect boxes with lines, I thought at first “what is this craziness and how can it possibly be used in a music software?” But after using it for a bit, discovering it’s quirks and just getting my head around how different things work, it dawned on me that this is actually a very powerful and unique programming paradigm.

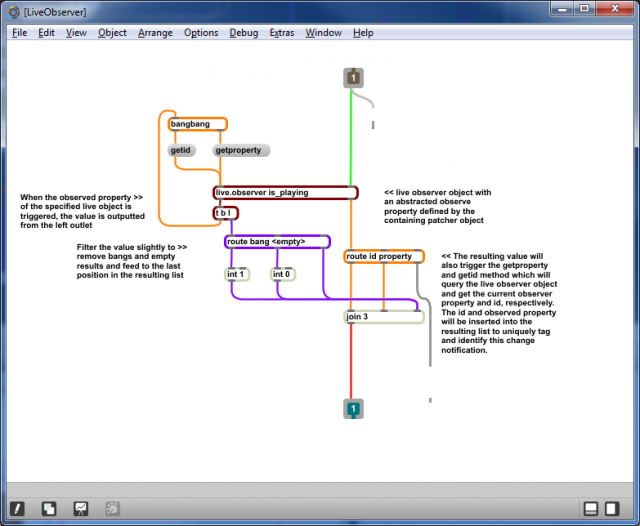

I took over the Max for Live proof of concept that Peter started and productized it in preparations for consumer consumption. I came in and was able to quickly learn the flow of logic since it’s so easy to see how the patch worked at runtime. This allowed me to clean things up and make the code more efficient, improving the way we interfaced with the Live Object Model. Max also provided me with the versatility of writing programming logic using Max objects, JavaScript as well as Java classes.

More recently, my primary focus is diving into the control surface portion of the Live Object Model. With control surfaces, we’re actually able to talk directly with MIDI devices like the Ableton Push. We’re able to take over buttons, assign our own behavior to them such as lighting and embedding Liquid Rhythm specific functionality.

It ties the Push hardware even closer into a user’s workflow, so they can quickly make a beat within LIVE, and then switch over into the Liquid Rhythm Max for Live patch, and increase the beat complexity with all the features that we provide without breaking the musical groove.

DB: Let me introduce Chris. Chris is our Junior Developer, but he’s growing more senior day by day. The Max for Live device platform is of great interest to us. So Chris took on an experimental project called VQ, which is a velocity shaper for MIDI. He prototyped and built a plug-in from design up to full product concept for us to test out how that system is going to work. So he’s going to explain his experience with that, and his introduction to Max MSP.

CM: I was looking to learn something new. Then I was given the pleasure of working with Max. So much like my good friend Hui, I just looked at all the boxes and I thought, “Whoa, this is something different.” We just connect and connect objects.

Eventually it started to hit that prototyping was really easy as opposed to programming languages that I worked with before. I don’t have to do much set up; all these objects are premade. So it’s very easy to just try your ideas and test it out fully.

Of course I couldn’t always find a pre-existing object. So that’s when we started diving into the world of MXJs and all that, to get the full functionality that you want out of something.

Eventually by digging around, and just bouncing off the walls, it ended up working.

DB: Although each of one of us takes on different projects, when we’re all in the main developer area we tell our war stories for the day. So I’ll come and say, “Hey, I found this new object, this, this, this,” or Chris will work at something and I say, “OK, that patch is way too messy and you’re using this technique. Try this instead,” so we’re able to exchange ideas. Hui taught me some tricks about color-coding his patch cords, which helped me out.

We have different philosophies and different things we bring to the table. We always look for things that work, despite the chaotic unpredictable circumstances to work in. So we’re constantly retooling and reworking things. We want to find the objects or the techniques that have made it through the first round of failure. Because, if we can test an idea and it can fail quickly and we can understand why, then we can re-implement that solution later on. And we can spread the knowledge through the company.

So basically, I solve some of the fundamental conceptual architectural issues with my designs and then I get together with Adil, the Lead Developer at WaveDNA, we communicate and figure out how to transfer prototypes into different commercialization stages, and then Peter, Chris and Hui handle different parts of our pipelines, and we can work in modular teams that way.

Dave, how about your personal experience with Max? You’ve had previous interactions with it?

DB: Personally, myself, I’ve been a huge Max-head, right from the beginning. I used to hang out at a store in Toronto, called Saved by Technology. It was a great place where every week some strange new thing came in.

Max just completely impressed me because I realized, here’s a language that you can use to build other things, using this world of objects and patch cords. And unlike most other programmers at the time, I was self-trained. I had no formal programming background.

As a kid, I used to program in DOS, in this modular language called Foxbase Pro that I used to structure data. Using that language, I was able to develop some of my early theoretical ideas.

That language was very modular. And there was a concept from that language that I was able to carry forward. It was the concept of indirection; that I was able to take a cell and change it’s assignment programmatically. So that means I could add dynamic placeholders to do functional things on my pre-existing data structures.

Foxbase Pro is dead and gone, but that concept stayed with me and that it’s a good way to work. So when I saw Max MSP come out, it actually was a perfect fit for my Foxbase Pro background, which is kind of cool. I had Max personally for a while, but I wasn’t sure what to do with it.

When did you decide to use Max to explore and develop your ideas leading to Liquid Rhythm?

As far as the first major business step towards what the company is today, actually began on 11/11/01. There was a Harvestworks convention in New York City and David Zicarelli was going to be speaking at this convention.

This was a developer conference, and that was the year I had decided to fully commit to starting things going. So my first business activity to move my business forward was to meet the wide world of Max people at this developer conference, and learn how to bring my concept to reality.

I get to the conference and there are maybe 12 people there. A woman named Daphne started the class, and people were creating a patch called Random Atonal Crap.

Now, for me as a software developer/prototyper, I was screaming on the inside “I don’t want to do this fluffy artistic performance stuff. I want some real, hard, like solid meat to get into.” I was complaining on the inside, and I think I even complained on the outside at one point.

But the highlight for me was when David Zicarelli came in. That was where he first introduced that JavaScript was coming to Max. He showed a prototype of that, and that totally opened the door for what’s possible today.

Later, I had dinner with David Zicarelli and I asked him, “How do I make an interface patch communicate to a business-layer patch?” So he showed me some things about coll objects and how to move data around. It was through that conversation and developing early prototypes that ultimately led to the company’s creation. It also informs and helps me manage my process today.

I imagine your use with Max has evolved over all these the years.

My role in the company is advancing the theoretical core of the Music Molecule. When I first started working on Liquid Rhythm, I did a lot of my designs on white boards and sketching things out. And because everything was new, I just let the designs go raw. There was a lot of improvisation in the early days and this led to a whole community effort of what Liquid Rhythm is today.

Now that we’re moving into our second product, I need to fully specify things ahead of the game because I want to introduce things in an ordered fashion. So how I use Max now, it’s essentially a living design document.

One of the programming design languages for structuring the object relationships —an old one that was pre-UML— was called Data Flow Diagrams, where you have data entities and they’re connected together by wire.

That was a great language for me to design in. But then when I look at Max, I can see that it is essentially a Data Flow Diagram. I view my Max programming as halfway between linear programming and designing an electronic circuit.

I try to have a fixed set of design tools when I’m prototyping. My goal for all of my code is that it must die a noble death. I write things to iterate through systems quickly, and I have to build a system with a current set of assumptions and get that working, knowing as I evolve and move on to other systems, that first system can fail.

So I count on all my code failing at some point, unless it has a screaming reason to stay alive. Sometimes the only purpose for things to come alive is that you can see how it works, you can see its moving parts, you watch how it falls apart and you study why. Then the next iteration around comes together in a better manner.

So by developing design processes using a few core trick tools that allow me incredible flexibility in building modules, I can build complete systems, rip them apart, rebuild them, rip them apart, and refine a very chaotic process in a very linear way.

With this latest incubating project involving a tonal patch, I have about 50 sub patches under the main project and all sorts of things working together. But the benefit of things right now is that with this fully specified patch in Max, now I have an ultimate knowledge transfer tool for the company.

I like that idea of a ‘knowledge transfer tool’.

For me it’s a living data document that allows us to specify our theoretical concepts.

So now, with this central Max document, one path is for it to turn into an Ableton Live patch. Another path is for it to add extension into the existing Liquid Rhythm program or Liquid Clips applications.

It can also be used as a living developer document. As opposed to saying, “Here’s a whiteboard sketch, God bless you and figure this out. And oh, by the way, you did it wrong,” I can now say, “OK, here, this works this way, make code that behaves like this.” And we can talk about that.

Now this shiny new thing that hasn’t been in existence before now has a way to communicate to everybody in a way that they can understand.

What was the inspiration for Liquid Rhythm, and especially the user interface?

DB: Well, the great thing that I saw lost between standard notation and MIDI was that standard notation allowed you to specify relationships between the notes in a compositional manner.

So if you scored a small motif —think of Beethoven’s 9th, if you like —you could then take the basic pattern material and re-deploy it under different transformations to create motivic variations that evolve that motif into a series of phrases or a full piece.

That allows people to put together complex structures. But if I take that same data that has all those relationships, and I take that same score and look at it in MIDI data, it’s now turned into chaos. You could see all of those relationships in standard notation, but when you look at that same information in MIDI, it’s gone. All you are left with is a spray of isolated notes — unconnected atoms instead of structured molecules.

Now the good thing about MIDI, it is performance accurate, and I can see what I play. But what MIDI leaves open is the question of why? Why should I put this note in this place as opposed to that place? Why should this note be this long, why should this note be this loud? Why, why, why? It’s all extremely arbitrary.

I spent 25 years looking at what’s between the MIDI notes. The spaces between the notes contain the relationships between note to note. And when you look at these relationships, you can decode and pose these relationships into a set of repeatable patterns.

The first layer of these patterns occurs at the eighth note. The second layer of these repeatable metric patterns, occur across a bar.

In wave theory, waves oscillate from strong to weak in a cycle. So with Liquid Rhythm we have two types of core waves. We have a binary wave, which alternates between strong and weak, and we have a ternary wave, which alternates between strong, medium, and weak.

We then use these core patterns to describe every temporal relationship across an eighth note, and across the bar at different resolutions. This turns into an adaptive grid.

Can you give us an example of how this grid works?

Well, the general problem that people have when they play in MIDI, is to record something into MIDI, and then want to quantize it. The problem is that music that is actually performed, rarely stays at one quant for very long. So now the question comes, at which quantization do I quantize it with? If I quantize at 16th, it’s going to match my 24th, and vice versa.

So the solution that the Music Molecules allows is an adaptive grid. Instead of you moving the music to a pre-existing arbitrary grid, we have an intelligent grid that finds your notes, where they are, and says, “Well, here’s relevant information.”

And once we can find the initial patterns that make up this underlying bar of music, within our coordinate system we can then allow you a rich set of permutations to transform your ideas.

What I find these days, in talking to people who talk about the philosophy of music making, is that with tools today like Ableton’s Push and various arpeggiators and what not, it’s easy for people to come up with their first idea. I can play around on a keyboard, I can bang out an idea, I can come up with something that sounds good.

The hard problem lies in how do I come up with my second idea, and how closely is it related to my first idea. When you look at blocks in space, that’s a completely arbitrary thing.

Our goal with Liquid Rhythm, on one hand is, yes, we want to introduce a tool that makes phat beats and helps people with what they’re doing. But really, my underlying motive is to introduce an interactive, intelligent music theory to help people see underlying design patterns in music beyond the MIDI data as traditionally shown.

All of the things I’ve touched on are explicit in our user-interface and our Music Molecule ‘data visualization and representation system’, so to speak, which evolved over a number of iterations.

We have other products in mind that are going to build on this theory. People that are using the tools in Liquid Rhythm, are going to see the same theoretical elements coming up in our next tools, and that will give them a bridge to understand our new conceptual developments.

We’re a music software company that makes no sound. But if we can give people ways to put notes in places where they normally can’t with MIDI editors, then that’s an interesting value proposition. It allows people to shape musical concepts beyond their playing capabilities, and I think that would open up all sorts of opportunities all over place.

Do you have any advice about starting an ambitious Max project?

DB: My advice is: keep plugging away at it — pun intended. Keep digging away and be prepared for large portions of your code die on the way to better solutions. It might be the wrong way today, but you’ll find the better way tomorrow. There’re so many projects and sub-solutions and bits and pieces of interesting code that you can take and use.

Now, on the flip side, that digging might take you into areas that you either didn’t want to go or might not want to explore. So you have to be willing to be an explorer, yet you have to be willing at times, to just settle down and say, “I’m going to make this JavaScript work whether it kills me or not.”

Finding that balance is what we talk about, so we kind of have a Max developer support group and say, “Yes, I screamed at my code again this week. I was horribly abusive, but I’m getting better.” So we give each other tricks for how to deal with things and then we move on from there.

HW: I wholeheartedly agree with Dave about digging. This language is one in which you just have to keep on going through it. over and over iteratively until you come across your solution. With Max, you are rewarded for tenacity.

Luckily there’s a global support group in the form of the Cycling ’74 forum where there is a gold mine of information. You’re never really alone because so many other people have the same challenges and problems.

You may not find a solution right away, but if you follow links and other’s suggestions, eventually you’ll come across something that you can think, “Oh, maybe that will solve my problem.” Very likely it probably won’t, but at least it will give you some new ideas to try. Because Max, as lovely as it is, will give you 10,000 ways to solve one problem. You never really know which is the best one, so you just hope that yours is good, and if it works, it works, and just move on.

I hear a lot about how generous the Max community is.

DB: In some ways, I think the camaraderie that comes in the Max community is that this is a community of people on the bleeding edge. Like everybody in the Max community, for the most part, is drawn to it because they want to try something that they’re not sure how to do in other languages, or haven’t been done before.

So of course people are going to run into problems and are screaming, because this is the land of trying things for the first time. It’s that overall sense of heroics with, “Wow, you’re a Max developer. God bless you.”

It’s really a philosophy as much as a coding language.

So, the big news, the release of a new version! Can you tell us about your new update?

Version 1.3.4 of Liquid Rhythm allows users to control the software with Ableton Push, offering producers and DJs a highly fluid workflow to keep creative juices flowing during the music-making process.

Taking advantage of Ableton Push’s ‘User Mode’, the WaveDNA team programmed a fully functional MIDI script that controls Liquid Rhythm directly from the Push hardware without ever having to touch the mouse. Users switch into Push’s User Mode to program beats in Liquid Rhythm v1.3.4, and switch back to the regular Push script to take full control of Ableton Live.

Thanks! We’ll be playing with this!